The real reason gear matters

How your photography gear affects your experience, style, and growth

Does gear matter? This seems to be a hot topic to debate but so many people throwing themselves into the fray keep missing the point of having gear in the first place: to explore and solve problems.

Sounds sciency! But exploration and problem-solving can be creative, artistic, and stylistic, not just technical. They could be about ergonomics and workflows too.

Even if its an emotional issue like feeling stuck in a rut, using different gear can often help you get out of that quickly.

But it’s not about finding shortcuts either. Rather, it’s about minimizing friction and maximizing progress.

What do I mean?

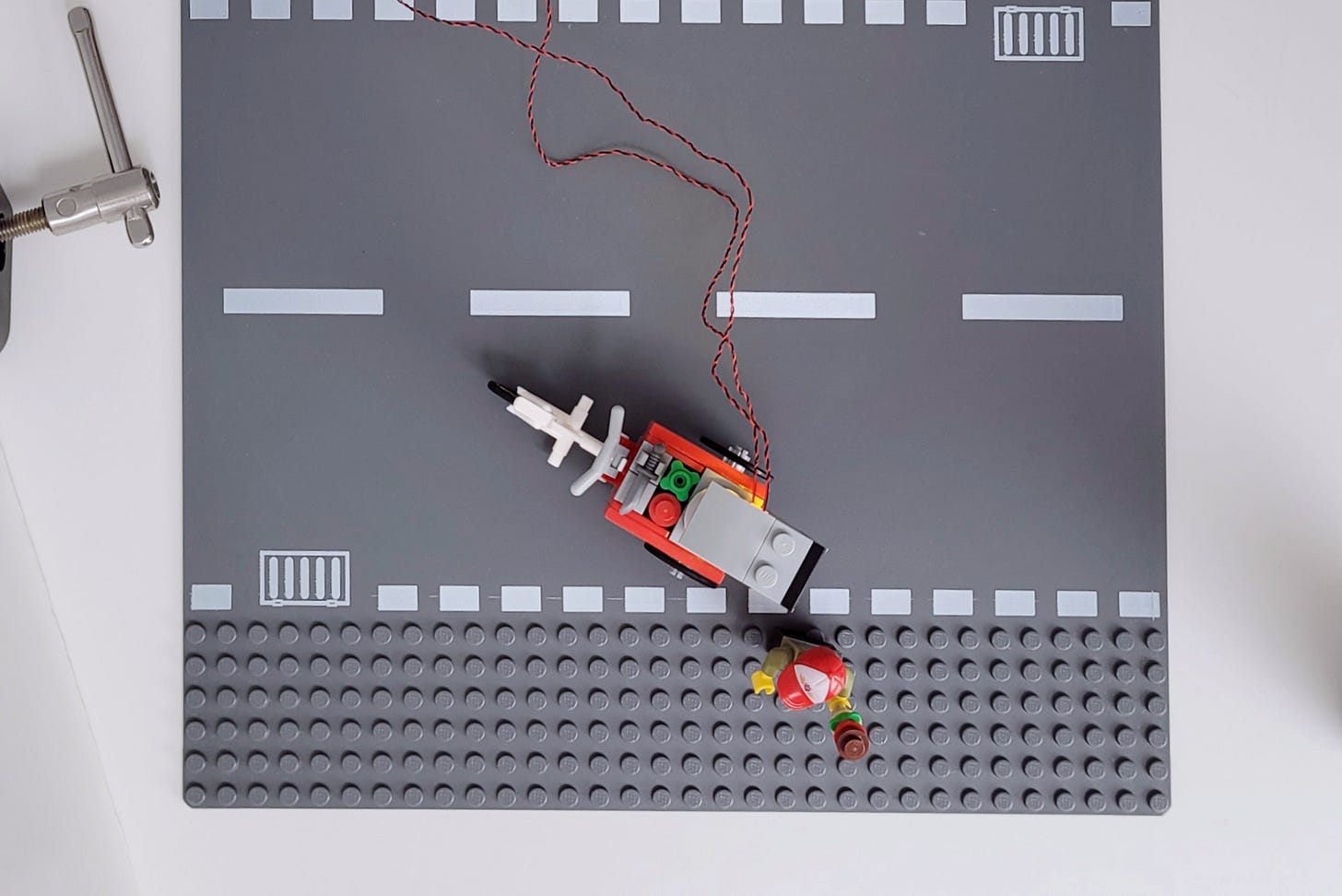

Well, let’s say I’m shooting my LEGO minifigs in my nook and I need to be hands-free as well as have my camera higher up for the composition I have in mind.

Do I want to go to my bookshelf across the room, pull out 8-9 books, rearrange the remaining books so they don’t all fall over like dominoes, carry those 8-9 books back to my shooting area, go back and forth looking for thinner or thicker books to get the right height, and then put my camera on the stack? Or do I just buy a tripod?

(God, I got tired just typing that.)

But true story; I used to do that a lot as I’m sure many of you have or still do.

I mean, on a good day, I used to do that.

On a bad day, I would just let the dread of the tedious setup (and cleanup, let’s not forget) deter me from shooting at all. Maybe I’d compromise the idea only to end up with a mediocre photo and feeling unfulfilled anyway.

But most days, whatever photo idea I had in my head would get filed away forever, and my camera would stay in the bag.

My social profiles from those early days are a testament to how very few times I actually pushed through the tedium to create the photo I wanted. I just took one picture a month, or every three months sometimes.

I knew I had to do something if I wanted to keep shooting LEGO more regularly so I bought a tripod, and that eliminated a huge friction point in my process.

It allowed me to set up faster, which not only got me shooting quicker, but shooting more. And the more you shoot, the better you get. The better you get, the happier you are.

That’s just one example of how getting some basic gear solved a workflow problem, made toy photography more enjoyable, and improved my skills.

Here’s another one that should be familiar: my ballhead kept slipping and messing up my composition all the time. So I’d frame my shot just a little bit higher then wait for my ballhead to settle into its final position. It was a lot of trial and error, especially when shooting with a macro lens— every millimeter counts.

Sometimes I didn’t want to mess around with the ballhead once it settled so I’d shoot the same photo over and over. I was constantly worried that I’d missed focus because I’d moved the camera ever so slightly by pressing the button.

If the composition was a bit crooked in camera, I’d tell myself to just straighten it in post rather than fiddle with the ballhead for another 10 minutes. Of course, I’d later realize that I didn’t move the whole tripod further back to compensate for the crop and would end up with a very unsatisfying photo anyway.

Stupid ballhead. It owned me.

So I bought a 3-way geared tripod head that allowed me to make tiny adjustments independently along x-, y-, and z- axes by turning knobs. This was a pricier investment but a game-changer, not just in terms of workflow but stylistically too.

I started playing around with different angles, moving around the set, focus stacking, and just letting myself become more creative because I was more confident in the support and had more control over my camera. Shooting toys was a lot more fun and I got to create more interesting photos.

My style evolved because the gear I had enabled me to do different things than before. It opened possibilities and made things flow faster and easier.

As soon as I understood that removing these small frustrations directly made me a better and happier photographer, I pretty much set about adjusting my toy photography workflow for maximum enjoyment wherever I could.

Now I ask myself these questions: What is stopping me from making a photo? What’s annoying me? What will fix that?

Here are just a few problems and their fixes off the top of my head:

It was really uncomfortable shooting with a phone at ground level (see main photo for the toy photographer plank), so I bought a camera with an articulating screen.

I wanted to include more of the background in my photos, so I bought a macro lens with a shorter focal length to get more DoF and wider field of view.

The light wasn’t where I wanted it when I wanted it, so I bought a flash.

There’s more but I think you get the idea. Lots of recurring problems I had, whether technical, creative, ergonomic, etc. were solved by gear.

But— and this is very important— I already understood photography enough that I was able to recognize the specific and recurring problems in the first place.

Specific meaning I can describe what I want in my photos in photography terms. I would like a wider field of view to have a more immersive look, for example.

Recurring meaning that I keep having the same problem. Otherwise, DIY or a workaround to the rescue for a one-off, which can be very fun in and of itself.

Then I would find a good and long-term solution by researching, which meant looking at lots of gear reviews for deep information to make an informed purchase. I wasn’t just randomly buying new gear, not knowing why and how it would help me.

That’s what I think the gear-doesn’t-matter crowd is really trying to say: more gear isn’t going to do anything for you if you don’t know what you want to do already. Gear shouldn’t be a substitute for understanding composition, light, and editing. They all work together.

But that’s our “curse of knowledge” bias at work:

The curse of knowledge is a cognitive bias that occurs when an individual, who is communicating with other individuals, assumes that other individuals have similar background and depth of knowledge to understand.

We have the benefit of hindsight so we want to save those down the line from wasting their time and money on unnecessary gear if the issue can be solved with creativity in other areas. Noble, but also kind of robbing them from finding their own way and own style through their mistakes.

So while well-intentioned, I don’t think it’s helpful to tell people, especially beginners, that gear doesn’t matter at all.

We all have to go through this process of discovering our style, and trying out different gear opens our eyes to what we enjoy and don’t enjoy. You don’t know until you try for yourself— and then try a few more times, really.

The same goes for composition, lighting, and editing, not just gear.

Second, telling beginners that gear doesn’t matter signals that it’s their limitation— when sometimes it’s the gear’s.

Case in point: many photographers want to get a photo of a sharp subject against a creamy, out-of-focus background (and foreground), especially phone photographers.

A very shallow depth of field is one thing that a phone camera can’t achieve due to the form factor and design though. That’s why there are AI portrait modes to fake it in processing.

But being beginners and having been convinced that gear doesn’t matter, they try in futility. It must be their lack of skill as a photographer that they can’t get a razor-thin depth of field because it can’t be the phone camera. That’s an unnecessary, frustrating, and demotivating exercise.

Any budget, consumer-grade DSLR or mirrorless camera with a kit lens can get a much more shallow depth of field than a phone camera. The gear does matter.

The leap from a phone to a DSLR or mirrorless camera is huge with just aperture control and ergonomics alone. There’s a drastic shift in approach, workflow, and style as well, seen below in these two recent photos by wendyverboom:

It’s almost as if the photos are from different photographers but it’s mostly a change from a dedicated camera to a phone camera. To be clear, the intentions and circumstances are very different as well: the photographer is on holiday, and opted to keep her kit and process minimal for travel.

But it’s not just phone-to-DSLR/mirrorless that can look and feel very different. The leap from a kit lens to a f/1.8 is also pretty big, I’d say, because that’s when the scene-stealing bokeh effects are available rather easily. A budget 50mm f/1.8 is often the next lens upgrade from a kit lens for that reason.

Bokeh is actually the default once we start talking about any macro lens because they’re designed to focus closely and magnify— the closer the lens to the subject, the more out of focus the background. That magnification, close working distance, and sharpness is why you buy a macro lens though, not for bokeh.

Sounds like the gear is doing a ton of work! Yes, but again— and this is very important— it’s the photographer who chooses the gear and knows how to use it well.

When we choose particular lenses, filters, or what-have-you, it’s because we want certain capabilities and effects available to use in our creative vision. Or we have different intentions and circumstances like with wendyverboom’s travel photos.

Choices that lead to a desired experience and outcome demonstrate skill.

I know a phone photographer who spends hours building elaborate scenes in studio or brings large models out to remote locations with infinite horizons and creates very impressive photos, but is always reduced to his gear.

"I can't believe you shot that with a phone!"

All the hours of prep, the smart use of the phone's strengths, the composition, the lighting, the practical effects, the editing-- all of that diminished because people just focus on the gear and the moment of shooting.

That phone photographer had the knowledge and skill; the commenter didn’t.

On the flip side, I know a few DSLR/mirrorless shooters who will hike to beautiful landscapes for a photo shoot only to tightly frame a single minifig and obliterate the rest of the scenery into bokeh. Zero sense of place.

I've done this before myself lol.

Now that's not a very smart use of gear, effort, time, and location. That look can be pulled off with a patch of moss on the ground and anything that has specular highlights in the background (see main photo taken in the park down my street).

Better gear doesn't automatically make a better photographer. Or more interesting photos for that matter. In fact, the less control you have with your gear, the more effort you have to put into composition, lighting, and editing in order to create great photos.

Gear doesn’t matter if you have a solid grasp of photography— settings, focal lengths, compostion, light, etc.— and are focused on just the result, not the experience of shooting or keeping your style.

Otherwise, gear matters. If it’s a pain in the ass to shoot or you don’t love the experience, what’s the point of a good photo? (I hope it’s not for internet points.)

Toy Photography Tips

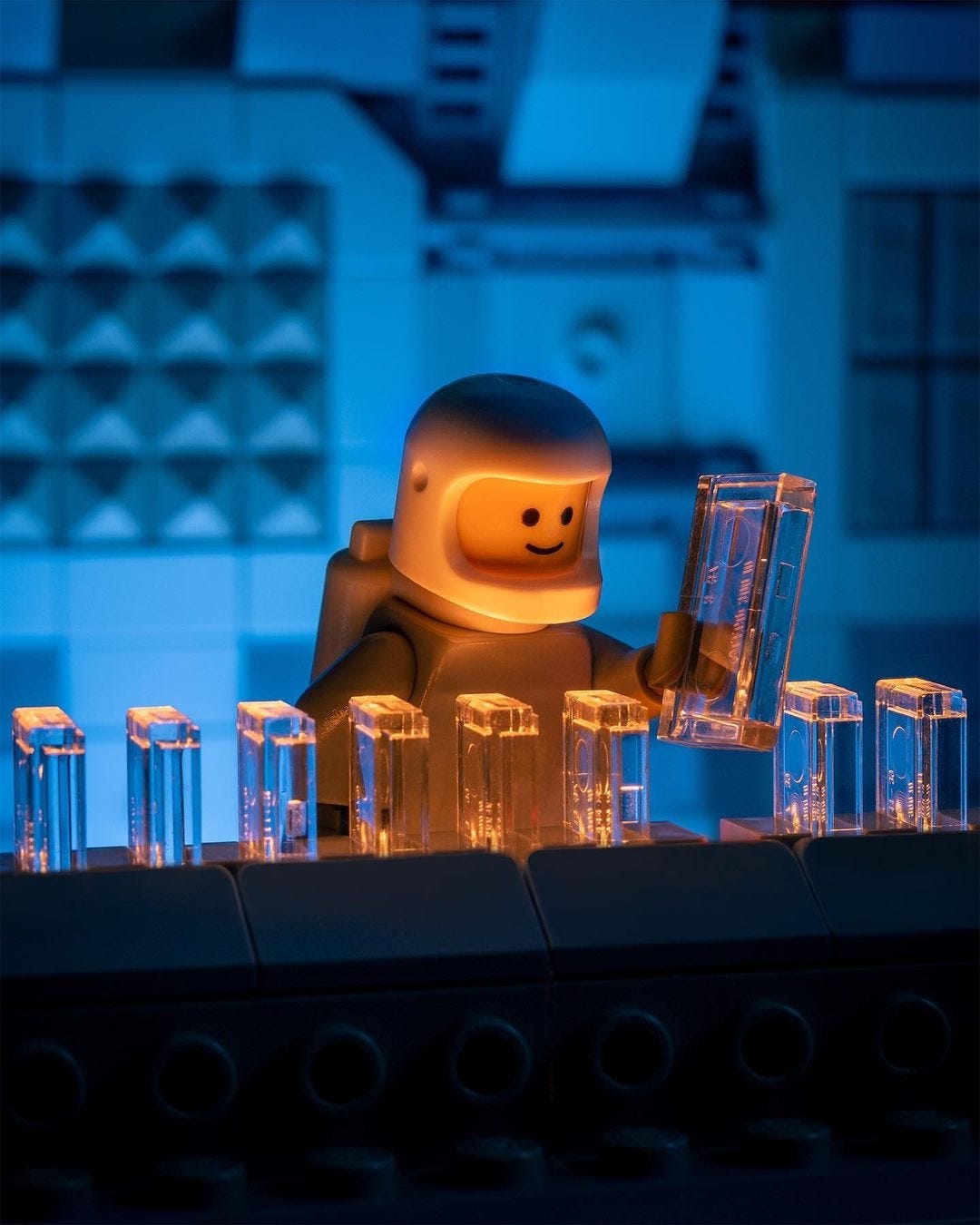

One of my favorite kinds of photos to shoot is a “nighttime” shot. They are lots of fun to shoot because you work with color and lights. They also look different from other LEGO photos that tend to be brighter, so they stand out to me and make me look longer.

Here’s my setup:

Lighting is simply a flash ($60) with a blue gel pointed at the back of the subject. Off to the side, I have a white foam board ($1) to bounce some of that light back onto the front of the subject.

You can probably see the reflection of the board in the minifig’s face. I don’t mind that too much but I did rotate that board to reduce that reflection as much as I could.

I also have practical lights ($10) in the kabob cart, tucked behind transparent orange tiles. Practical lights just means they are sources of light that are actually in the scene, versus my flash which is not in the scene.

On my camera, I had my vintage Takumar 50mm f/4 macro lens ($100) with a tilt adapter ($30).

Since this issue is about gear, let me explain how this peculiar thing works and how it enabled me to realize the idea in a photo.

I specifically chose this lens and adapter because I wanted to angle both the minifig and his cart and have them both in focus while throwing the background out-of-focus.

The tilt changes the plane of focus:

If I used a regular lens wide open instead of a tilt, I would only get the minifig in focus and not the cart.

How else might I problem-solve without the tilt adapter?

Stop down, but then I’d need a lot more light and I’d get more of the background in focus too.

Change the position of the subjects so they’re on the same plane, but that changes the composition to one that’s less interesting.

Move the background further back, but then I would need more buildings to fill up the space.

Focus stack, but then I can’t use atmospheric effects because they are random.

All of those are good solutions but would create more work for me or change my idea significantly. Gear matters.

Toy Photography Features

Here are some other cool “nighttime” LEGO photos to enjoy. Love those blues and interesting lighting!

Always love reading your articles. As usual a few aspects really hit home and get me thinking. Set up and tidy up are real demotivators for me and often stop me from shooting.