Dear beginners, lighting and editing aren't shortcuts

A solid idea and visual design are more important to the success of a photo.

A mistake I see beginner toy photographers make over and over again is skipping the basics and diving into lighting and editing too soon. They witness how both can transform a photo, and they naturally want to see that kind of improvement in their work too.

What beginners don’t realize though is that these photos that are lit and edited were already good to begin with. They were on the last two steps of the process. The concept and composition were formed in the first two steps, but weren’t demonstrated or explained. (More on that in a minute.)

The “story”, the shapes, the colors, and how the photographer wanted to lead a viewer’s eye or make them feel had been decided and put in place before any lighting was set up.

Lighting and editing build on the concept and composition of a photo, not the other way around. They’re the cherry on top of the cake— the thing that makes something good even better.

But if the concept and composition are weak, then all lighting and editing can do is polish that turd.

Coming up with ideas

To avoid polishing turds, start with a good concept.

Coming up with ideas is the hardest part, especially if we add the pressure of trying to be unique. Instead, ask yourself these questions:

What or who is the subject or “hero” of the photo? What are they doing? Where is this happening?

If you came up with “a Stormtrooper standing on moss”, try harder. That’s a low-effort and hackneyed idea. To be fair to Star Wars fans, any kind of LEGO minifig just standing on moss is likely going to make for a very dull image.

I’ve done my fair share of minifigs-on-moss photos so I know first-hand how boring those can be to look at after the first dozen or so.

When I’m in one of my “mossive” moods (huge thanks to The APhOL for that term), I don’t dismiss it right away but I try to complicate the idea a little bit instead.

I make my subject interesting, for one thing. Almost all of the subjects of my LEGO photos are something I concocted myself, so they’re not common.

I do have a soft spot for Black Falcons which are popular minifigs. So to make them interesting to me as a subject, I might go for three or four as a group instead of shooting a single minifig.

Every LEGO photographer knows what a chore it can be to get one minifig positioned on a spongy material like moss, so having a handful of them arranged carefully on it is also something special.

Complicating a mossive photo even further, I might shoot a different kind of subject altogether like a building or vehicle. Even more interesting? A MOC.

That’s just one way to come up with a concept. There are so many other seeds for ideas, not just having an interesting subject. A new or unusual accessory or prop sparks ideas for me too, for example.

Have an idea and then just change it up a bit for starters. “Get the cliche out of the way” as one of my favorite photography podcasters likes to say and do your mossive photo (or everyday Stormtrooper scene or raspberry afro shot), but then iterate.

Shifting teaching gears to design

This year, I’m taking a more holistic approach to my teaching by including how to come up with an idea and how I want things to look so other toy photographers can get used to seeing that part of the process and not just the “magic”.

It’s easy for beginners to believe that lighting and editing are magic bullets for bad photos because there are loads of material teaching those two topics online.

The reason there aren’t a lot of tutorials about creativity and composition is because they can be difficult to cover. Also, just the word “composition” makes people’s eyes glaze over so let’s call it visual design instead. Same same.

I’ve mostly done lighting and editing videos because I deeply enjoy both those parts of my LEGO photography workflow, but also, they’re a heck of a lot easier to walk someone through. If you do this, that happens. The cause and effect are clear.

But I’ve finally found a way to include creativity and visual design in my YouTube videos that’s fun for me to do but also adds a lot of value for the viewer: showing my minifigs or accessories and marking up photos.

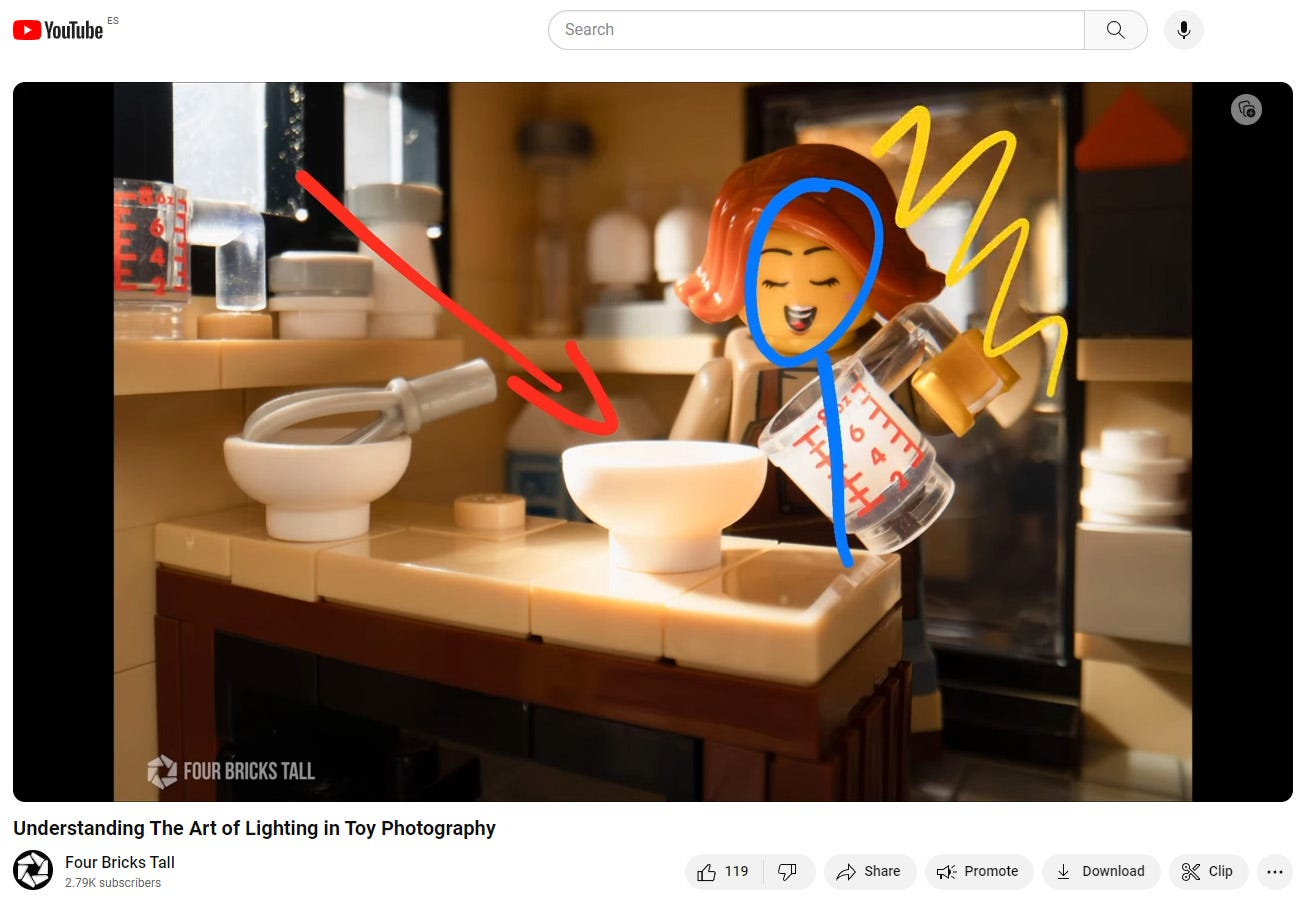

For example, in my video Understanding the Art of Lighting in Toy Photography, I immediately start describing the hero of my photo, what accessory she’s using for what action, and where it’s happening.

I’m showing how I thought about the concept first before jumping right into the lighting explanation: it’s the order of operations.

I’m doing something similar on my blog posts as well. In How-to Create a Wintery Scene and Cold Weather Effects, I dedicated an entire section to coming up with ideas and arranging elements in the scene.

When coming up with ideas for LEGO photos that are more than minifig portraits, I ask myself who is doing what, where, and why. The answers help me form a concept which then informs what I need for the shot.

The concept of this LEGO photo was a Viking setting up a campfire outside of his tent in the middle of a barren and snowy forest to provide light and heat.

Who? A Viking. Doing what? Setting up a campfire. Where? A barren and snowy forest. Why? For light and heat.

I briefly explained some visual design techniques I used and marked up the same photo a few times to make them easier to understand:

I even have a new photography group on Flickr that does markup and commentary every Tuesday.

MiniPics is a small group of passionate miniature photographers who post a photo they like on the discussion forum and talk about the creative choices we imagine the photographer made.

The insights given by the group can be really eye-opening even when the photographer themselves had no intention of using a particular composition technique visual design principle when they created the photo.

Hopefully these three new things I’m doing— the YouTube video format, the blog post structure, and the Flickr group— will give beginners a better understanding of how important concept and composition are to a photo.

Go back to the basics

If you’re a beginner photographer, the best thing you can do is nail visual design. If you can do that, you can work with any gear, be it a phone or a high-end mirrorless, and still come up with really great photos.

Design is the single most important factor in creating a successful photograph. The ability to see the potential for a strong picture, then to organise the graphic elements into an effective, compelling composition has always been one of the critical skills in making photographs.

- Michael Freeman, The Photographer’s Eye

Understanding composition is also useful later to lighting and editing because you apply the same kind of thinking when placing lights or adding radial gradients, for example. These are all just design choices made by the photographer to direct a viewer’s attention somewhere and make them feel something.

LEGO Photography Contest

I mentioned somewhere that new and unusual accessories or props spark photo ideas for me and that’s especially true of custom parts.

I created this photo around that magnificent measuring cup by Brickrock Press:

They have a ton of stuff in their shop that I think LEGO photographers could have a lot of fun with like I did. So how would you like a chance to win some?

We’re having a LEGO photography contest this month where you could win $20 worth of custom-printed LEGO parts with free shipping from the US to anywhere in the world where it’s legal.

To enter the contest, submit a LEGO photo (up to 3) that fits any of Brickrock Press’s product themes: space, city (including automotive, hazmat, and pop culture), and pirates.

Share your photos, new or old, on Instagram or Discord before Feb 29, 2024 22:00 CET! Click the button below for the rules and more details.

Good luck!

I was rereading this piece this morning, and this stuck out:

"When coming up with ideas for LEGO photos that are more than minifig portraits, I ask myself who is doing what, where, and why. The answers help me form a concept which then informs what I need for the shot."

My brain added "And this is storytelling in a single, static, and silent image." Because that's what we do, right? Try to convey a story. And how can we successfully do that if we haven't thought it through, as you describe? It's like shooting a music video for a song you've never heard.